Clementine Hunter and the Melrose Plantation

Self-taught Artist | Paintings | Restored/preserved -- Open to the public

Black businesswoman Marie Therèse Coincoin created this plantation, includes perhaps the first black for black designed buildings in the United States.

This is one of the largest plantations in the United States built by and for free blacks. The land was granted to Louis Metoyer, who had the "Big House" built beginning about 1832. He was a son of Marie Therese Coincoin, a former slave who became a wealthy businesswoman in the area, and Claude Thomas Pierre Métoyer. The house was completed in 1833 after Louis' death by his son Jean Baptiste Louis Metoyer. The Metoyers were free people of color for four generations before the American Civil War.

As the children of a French-American father and African mother, Louis and his siblings were considered multiracial "Créoles of color." Similar to the Metoyer siblings, many multiracial Creoles became educated property owners, particularly in New Orleans, Opelousas, and the Cane River and Campti areas of Natchitoches. Although not legally freed by his white father until 1802, Metoyer evaded Louisiana's Code Noir that prohibited enslaved men from being granted land. This was probably due to his father's wealth and standing.

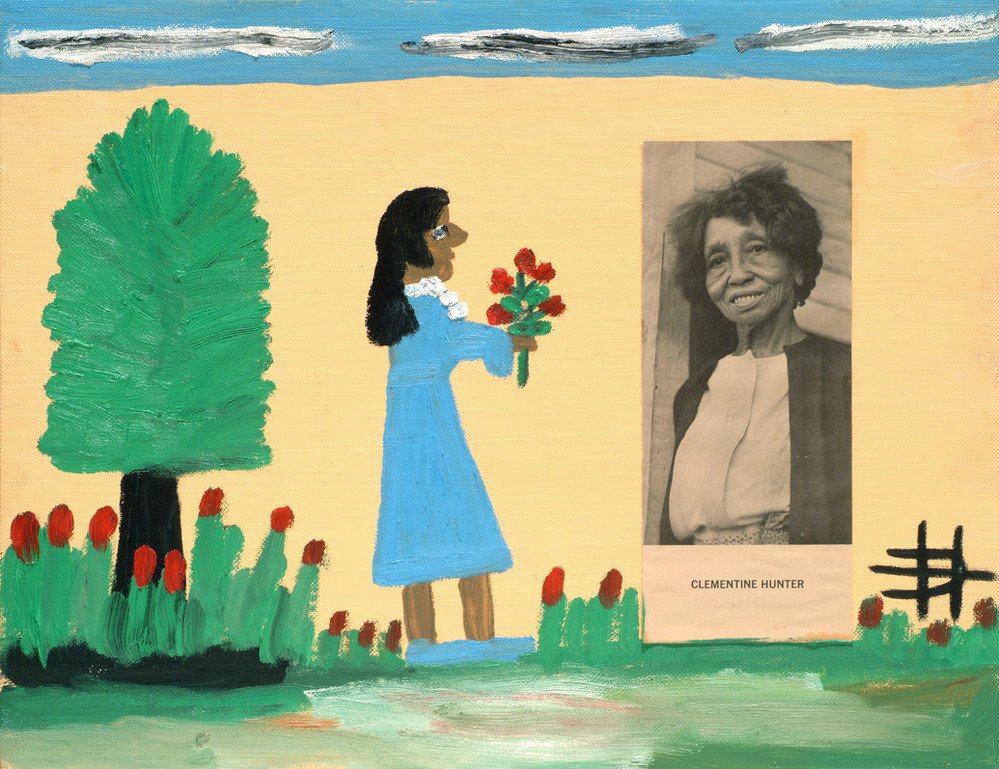

Clementine Hunter

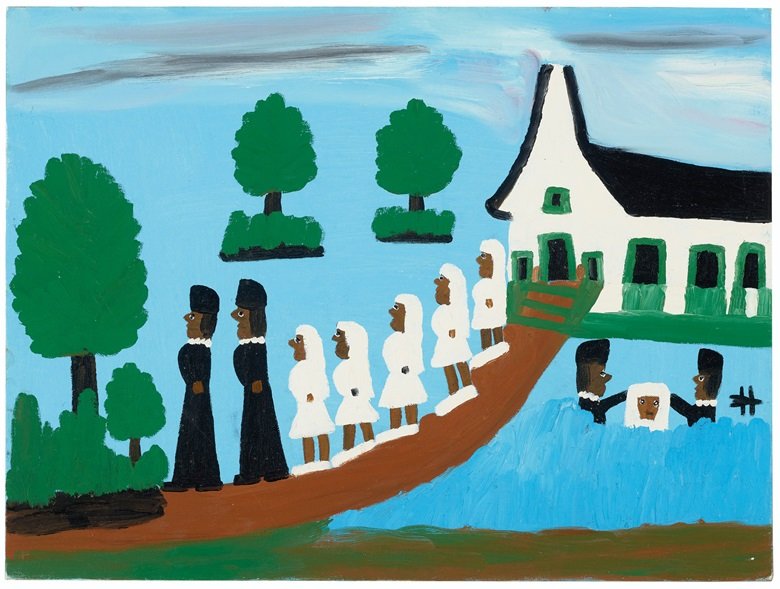

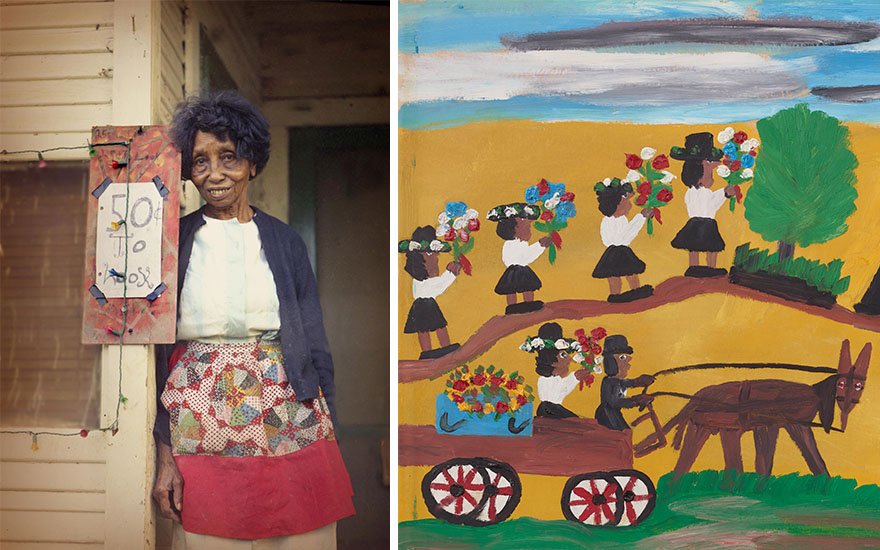

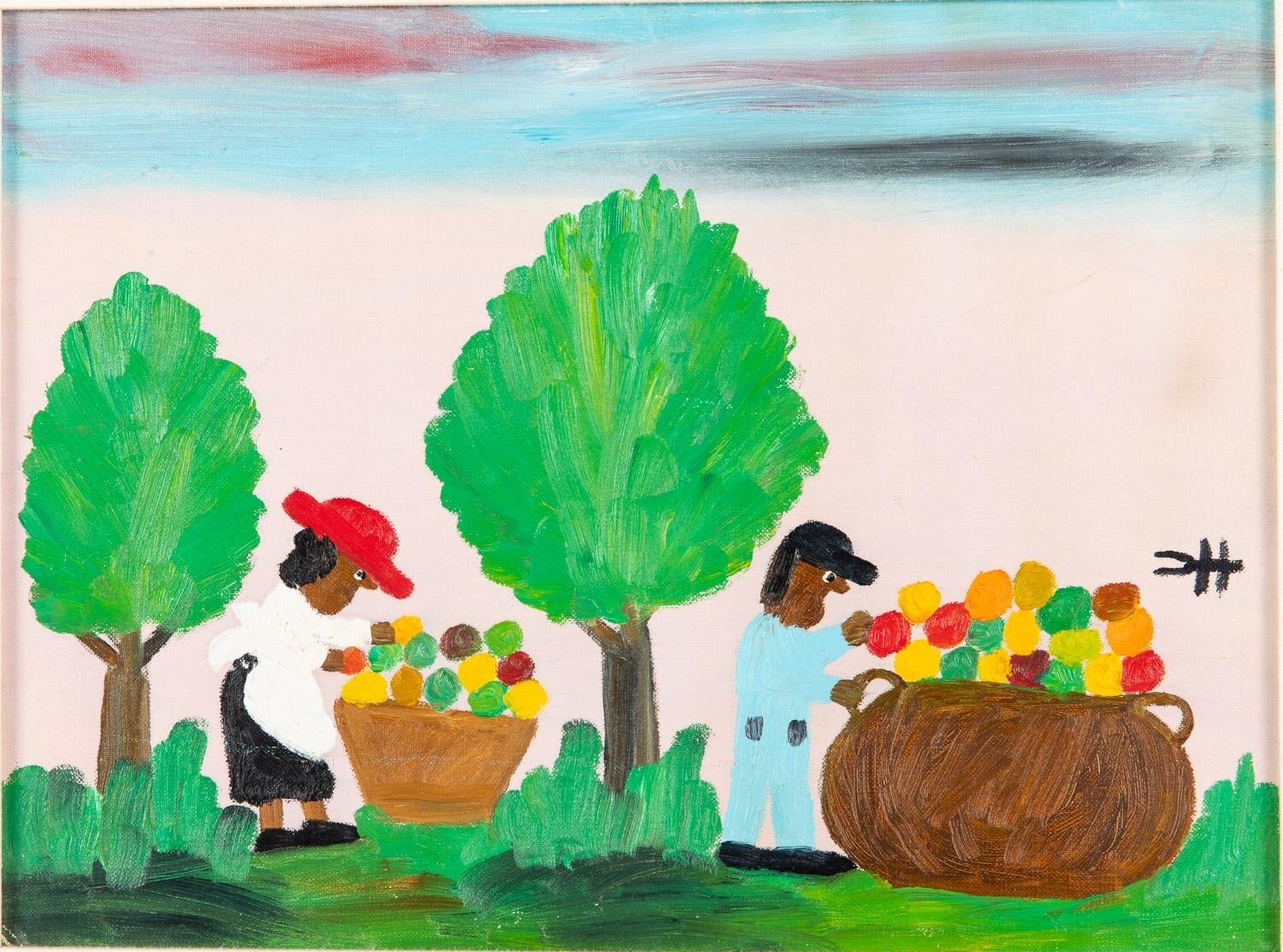

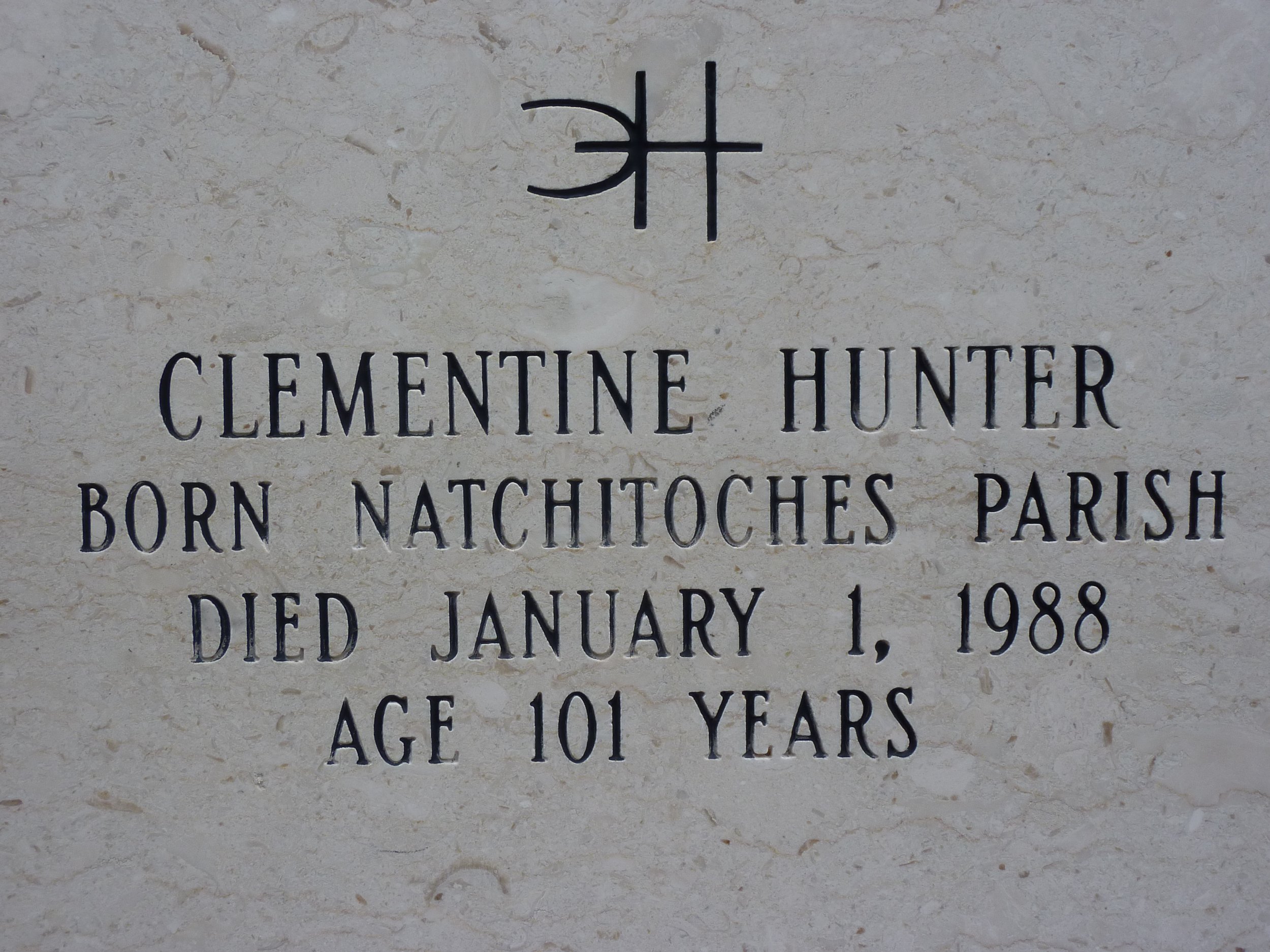

Clementine Hunter (pronounced Clementeen) (late December 1886 or early January 1887 – January 1, 1988) was a self-taught Black folk artist from the Cane River region of Louisiana, who lived and worked on Melrose Plantation.

Hunter was born into a Louisiana Creole family at Hidden Hill Plantation near Cloutierville, in Natchitoches Parish, Louisiana. She started working as a farm laborer when young, and never learned to read or write. In her fifties, she began to sell her paintings, which soon gained local and national attention for their complexity in depicting Black Southern life in the early twentieth century.

Initially she sold her first paintings for as little as 25 cents. But by the end of her life, her work was being exhibited in museums and sold by dealers for thousands of dollars. Clementine Hunter produced an estimated 5,000 to 10,000 paintings in her lifetime. Hunter was granted an honorary Doctor of Fine Arts degree by Northwestern State University of Louisiana in 1986, and she is the first African-American artist to have a solo exhibition at the present-day New Orleans Museum of Art. In 2013, director Robert Wilson presented a new opera about her, entitled Zinnias: the Life of Clementine Hunter, at Montclair State University in New Jersey.

In 1902, around the age of fifteen, Hunter moved to Melrose Plantation.

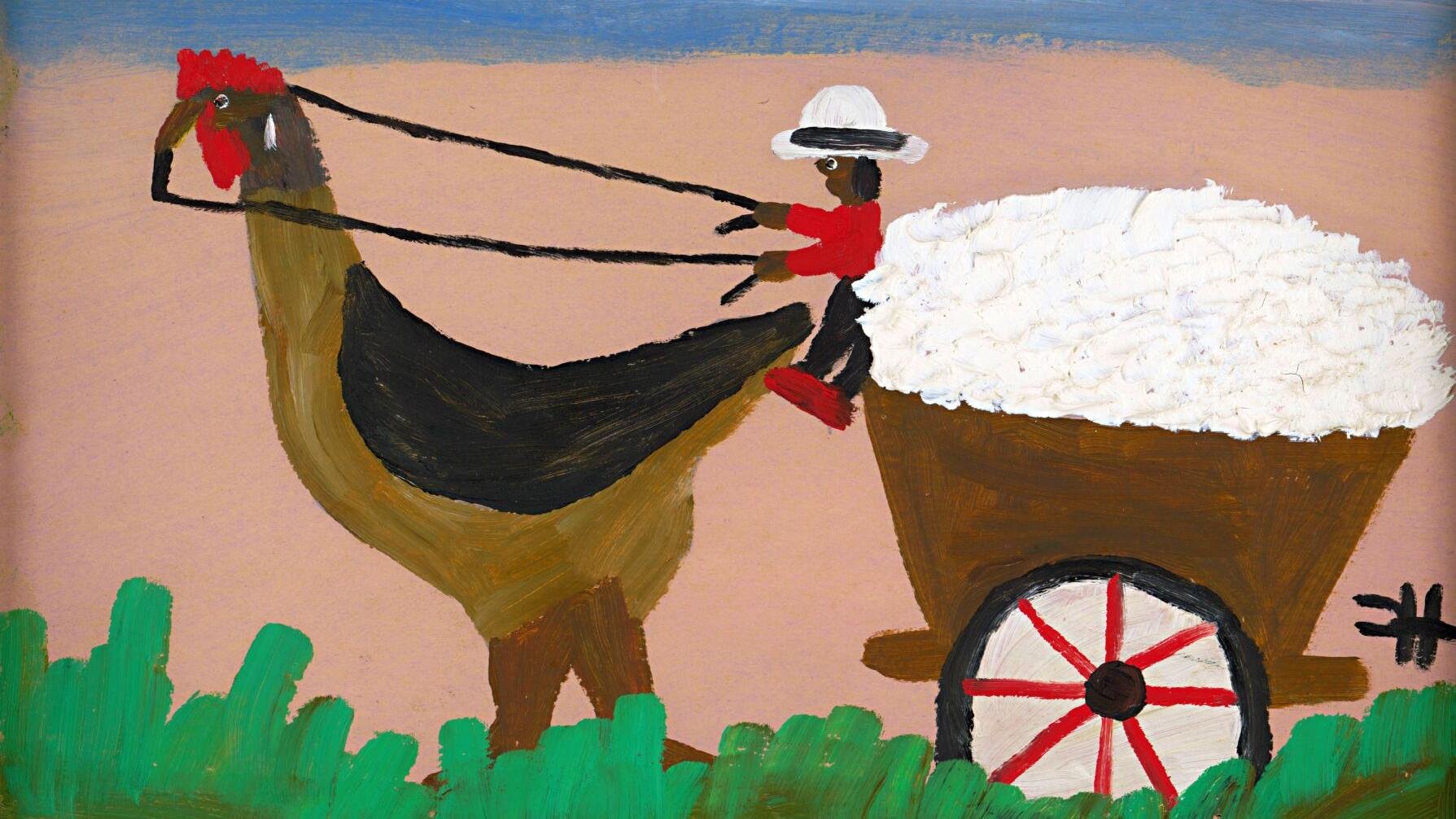

Hunter's father, Janvier "John" Reuben was hired as a wage laborer by John H. Henry, the current owner of Melrose. Hunter also worked for a wage as a agricultural laborer, harvesting 150 to 200 pounds of cotton a day, making 75 cents. In the fall, she would also harvest pecans, working six days a week for months of the year. While in her teens, Hunter took informal classes at night with other workers at Melrose Plantation. Her mother, Mary Antoinette Reuben, died in 1905 at Melrose.

When Hunter was about twenty in 1907, she give birth to her first child, Joseph Dupree, called Frenchie. Hunter's first partner was Charles Dupree, a Creole man about fifteen years Hunter's senior. Charles is rumored to have built a steam engine with having only seen a picture and was well known for his highly skilled labor. Their second child, Cora, was born a few years later. Charles Dupree and Clementine Hunter never married, and Dupree died in 1914.

In 1924, Clementine married Emmanuel Hunter, a Creole woodchopper at Melrose six years her senior. Until Clementine Hunter married Emmanuel, she spoke only Creole French, and he taught her American English. The two lived together in a workers' cabin at Melrose Plantation and had five children, although two were stillborn. Hunter's children were named Agnes, King, and Mary, although she called Mary "Jackie". On the morning before giving birth to one of her children, she harvested 78 pounds of cotton, went home and called for the midwife. She was back working a few days later.

In the late 1920s, Hunter began working as cook and housekeeper for Cammie Henry, the wife of John H. Henry. She was known for her talent adapting traditional Creole recipes, sewing intricate clothes and dolls, and tending to the house's vegetable garden. Before long, Melrose evolved into a salon for artists and writers in this period, hosted by Cammie Henry. In the late 1930s, Clementine Hunter began to formally paint, using discarded tubes from the visiting artists at Melrose.

Credit: Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Melrose_Plantation

Creator: Clementine Hunter (late December 1886 or early January 1887 – January 1, 1988)

Creation date: 1940s-

3533 LA-119

Melrose, LA

(318) 379-0055

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Melrose_Plantation

-

Books

“Clementine Hunter: American Folk Artist” by Art Shiver and Tom Whitehead (LSU Press, 2012)

“Clementine Hunter: Her Life and Art” by James L. Wilson (Pelican Publishing Company, 2012)

“Painting by Heart: The Life and Art of Clementine Hunter, Louisiana Folk Artist” by Shelley Orr (Harry N. Abrams, 2000)

Clementine Hunter: Her Life and Art, by Art Shiver and Tom Whitehead, University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press, 2008

Clementine Hunter, by Tom Whitehead and Art Shiver, Pelican Publishing Company, 2003

Clementine Hunter: Memory Painter of the Cane River, by Art Shiver, Louisiana State University Press, 2001

Clementine Hunter: The Life and Work of a Louisiana Folk Artist, by Art Shiver and Tom Whitehead, Art Shiver, 2000

Clementine Hunter: The African-American Impressionist, by Art Shiver and Tom Whitehead, Louisiana State University Press, 1999

Magazines

“Clementine Hunter: A Life Remembered” by Jodi B. Derouen, Louisiana Cultural Vistas (Winter 2018)

“Clementine Hunter: The Grand Dame of Louisiana Folk Art” by Susan Strickler, Folk Art Messenger (Spring/Summer 2012)

“Clementine Hunter: From Cotton Picker to Acclaimed Artist” by David Johnson, The Louisiana Weekly (November 18, 2019)

"Clementine Hunter: The Life and Legacy of an African American Artist," by Rachel Thomas, Southern Living, October 2018

"Clementine Hunter," by Nancy Collins, Louisiana Life, May/June 2018

"Clementine Hunter: A Painter’s Life," by Laura Beach, American Style, December 2017

"Clementine Hunter: The Life and Art of a Louisiana Legend," by Tom Whitehead, Louisiana Cultural Vistas, Spring/Summer 2017

"Clementine Hunter: A Louisiana Legend," by Mary Ann Sternberg, Louisiana Cultural Vistas, Autumn/Winter 2000

Online Resources

Clementine Hunter: The Life and Work of a Louisiana Folk Artist, by Art Shiver, Art Shiver

Clementine Hunter website: https://clementinehunterartist.com/

National Museum of African American History and Culture: https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/collection/search?edan_q=Clementine+Hunter

New Orleans Museum of Art: https://noma.org/artist/clementine-hunter/

Smithsonian American Art Museum: https://americanart.si.edu/artist/clementine-hunter-2176

The Historic New Orleans Collection: https://www.hnoc.org/our-collections/online-catalogs/clementine-hunter-online-catalog

Louisiana State Museum: http://www.crt.state.la.us/museum/louisiana-state-museum/clementine-hunter-gallery.aspx